“I’ve done a lot of thinking about political processes,” Tepper explains. “Isn’t it curious how most people think their taxes are too high, yet we elect people who continue to raise our taxes? There’s a paradox in there somewhere, and so that means there’s an interesting gameplay element to exploit.

“In ATITD, players can pass pretty much any real-life law that could be enacted in the game. Will similar things happen? Will we end up with laws that nobody likes?”

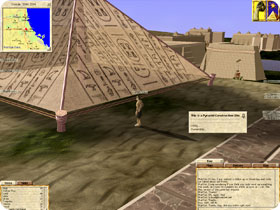

Taking in the Sights. Notice the icons in the upper right. The bucket indicates you can collect sand here. Click the sun-topped pyramid to see your progress in the seven schools’ tests.

Stranger in a Desert Land

A Tale in the Desert II is actually the second go-around for a saga set in ancient Egypt. Tepper plays the role of the Pharaoh, who oversees the game world and announces important events, such as upcoming Demi-Pharaoh elections. A mysterious character called The Stranger opposes the Pharaoh, telling him:

“You are nothing but an oppressive dictator. You abandon your people at the mercy of these wild lands. You have built us schools and universities, yes. Yet you extort such vast donations and fees from us in the name of research and tuition. All this when you live your life in luxury with riches beyond what we dream of. And yet, you claim to be a friend. I could not but laugh at it. Stop oppressing us with your rule.”

“There’s truly a feeling that everyone in Egypt is working to make the game better. Passing a law is difficult, but it’s among the most rewarding things you can do in the game. When you introduce what ultimately turns out to be a successful law, you’ve left your mark on Egypt in the most permanent way possible.”

- Andrew Tepper, lead designer

Working with the universities that teach skills in the seven disciplines, The Stranger has created seven tests for each, with the ultimate goal of allowing the citizens of Egypt to build their own world outside the Pharaoh’s decrees. Thus Tepper plays his own personal libertarian philosophies against the controlling characteristics he finds intrinsic in human nature, curious how the clash will play itself out.

Hambone. Players dance around a sculpture. We’re not sure if they’re expressing approval or disapproval.

Leaving Your Mark

Tepper relates an anecdote from Tale I that neatly sums up this clash: “The Stranger had introduced a number of technologies that allowed for great efficiency gains but could be abused in ways that made all of Egypt suffer. Clear-cutting was a way to harvest massive amounts of wood at a time, but it killed the trees in question for one real-life week.

“Do games that reward solo play evolve a cooperative or individualistic culture? I’d bet the latter”

- Tepper

“The players invented a law that said if a tree is harvested three times normally in a 10-minute period, then it is marked as protected for the next week, and clear-cutting protected trees would be illegal. I thought this was an amazingly creative solution to the problem.”

That situation leads Tepper to remark: “There’s truly a feeling that everyone in Egypt is working to make the game better.”

Game Hardware

Check out our systems for your best gaming experience.

- Site: A Tale in the Desert II

- Publisher: eGenesis

- Genre: Massively Multi-Player Online Role-Playing

“Isn’t it curious how most people think their taxes are too high, yet we elect people who continue to raise our taxes? There’s a paradox in there… and so that means there’s an interesting gameplay element to exploit.”

- Tepper

Tepper continues, “Passing a law is difficult, but it’s among the most rewarding things you can do in the game. When you introduce what ultimately turns out to be a successful law, you’ve left your mark on Egypt in the most permanent way possible.”

With Great Power Comes…

While the game emphasizes cooperation among players, anyone who has played a game online against live opponents knows that competition over even the most inconsequential things can be fierce. Egypt is full of resources that players can gather and use to build ever-more-elaborate buildings and tools — some as part of tests and others just to improve their characters’ skills — but ultimately they won’t get very far if they don’t like to share. Tepper has hit upon a few reasons why most ATITD gamers don’t mind playing nice with others.

Welcome to Woodshop. A wood plane is an essential tool that turns the wood you collect into boards needed to build all sorts of things.

“Players are more cooperative than I would have predicted before the game launched,” he says. “Part of that may be that we tend to have a more socially mature crowd than most online games. Another part is probably that the cooperative game elements tend to create a cooperative culture in the game. This is a testable hypothesis: Do games that reward solo play evolve a cooperative or individualistic culture? I’d bet the latter.”

Certainly the ultimate test of that hypothesis is the Demi-Pharaoh election, which caters to individualism but also requires players to be willing to elect someone who can be trusted with the power to ban others. (Not all elections result in a new Demi-Pharaoh.) While the ban affects a specific character — not the player, who can come back as a new character — Tepper notes that “such [an action] effectively erases months of effort. I imagine that few players would accept such a loss and come back.”

Beautiful Morning. A prosperous neighborhood built completely by players.

Between both renditions of the game so far, nine Demi-Pharaohs have been elected, but none have used the power. However, Tepper says “it would not surprise me if that no longer holds true by the end of Tale 2. At every Demi-Pharaoh election there is a debate about what constitutes an acceptable use of the power.”