A Brief History of Chess

From Egypt under the pharaohs to the Roman Empire to Emperor-controlled China, board games have long been part of the culture of civilized societies. While the origins of chess are murky, a seventh century Persian poem gives India credit with its invention. According to the author, chess came to Persia (modern-day Iran) during the mid-500s.

During subsequent centuries, chess morphed from its original form to the one we know today. The Indian version of the game, which was known as chaturanga, featured a king with an adviser by his side, flanked by elephants, horses and chariots. A row of foot soldiers held the front line. The rules, however, were different in many ways — for example, castling was not allowed, and you had to either capture your opponent’s king or take all of his pieces except the king to win.

When the Moors invaded Spain in the eighth century, the game came to Europe. The Muslim leader Haroon al Rashid gave a chess set to Charlemagne as a gift, and Vikings brought it to northwestern Europe during their travels. By the 11th century it had arrived in Germany, and from there chess found its way to England and Ireland.

An Ever-Evolving Game

In the eastern world, chess migrated from India to China sometime in the eighth century, although some scholars believe it arrived hundreds of years earlier. It was played differently in China, however, with a river running through the middle of the board and players moving pieces along the intersections of the squares, as opposed to inside them. The game came to Russia from China, although western influences prompted the Russians to play it the way Europeans did.

During its travels, chess began to evolve according to the culture of its recipients. Misinterpreting the cloven tops of the Indian elephant pieces, which were meant to symbolize the animal’s tusks, players thought they looked like a bishop’s miter and renamed them. The Moors had already turned the chariots into castles, and the Europeans assumed the horses were knights on horseback. The adviser became the queen.

In 1,000 AD, boards with alternating white and black squares appeared in Europe, the first of many modifications to the game. Later, players added the to option to move pawns two spaces on their first foray into the action, and soon someone invented the en passant move, which enables a pawn to capture an opposing pawn that passes it by during a two-step opening move, as if it had moved one square.

During the late 1500s, the queen became the most powerful piece on the board, able to move in any direction for any distance. Around the same time, bishops, which were previously limited to one square per move, could now travel as far as players wanted along a diagonal line. These changes were made with an eye toward speeding up games, which had a tendency to last dozens of moves and produce frequent stalemates.

After that flurry of activity, the rules settled down and the game grew in popularity, with Spain becoming the center of chess culture before giving way to France in the 18th century. London took over around 1840 and hosted the first international chess tournament in 1851. Players began to develop sophisticated strategies; soon one’s opening move signaled the type of strategy one was attempting, although chess enthusiasts often switched strategies during games as circumstances changed.

Coming of Age

The 20th century saw chess reach its maturity. The Federation Internationale des Echecs (FIDE), or World Chess Federation, was founded in Paris in 1924; it’s typically referred to by its French acronym. While the FIDE was started as a non-political organization, it experienced problems because the Soviet Union refused to join — the game was incredibly popular in the communist country, which saw chess as inherently political. However, when Russian grandmaster Alexander Alekhine died in 1946, the FIDE announced a tournament to find a replacement, forcing the Soviet Union to join the process.

Mikhail Botvinnik took over the title after Alekhine, continuing Russian domination of the game that ended with Bobby Fischer’s defeat of Boris Spassky in 1972. In 1975, however, the notoriously reclusive Fischer couldn’t agree to terms for a contest against Anatoly Karpov, making Karpov the new world champion by default. Garry Kasparov took the title from Karpov in 1985 and successfully defended it until 1993, when he left the FIDE to start his own organization, the Professional Chess Association (PCA).

Grandmaster Nigel Short joined Kasparov in his endeavor and lost to him in the PCA world championship match, while the FIDE’s finals saw Karpov defeat Jan Timman. The two organizations, now bitter rivals, ran their own tournaments for the next three years. Kasparov beat Viswanathan Anand in 1995 while Karpov won against Gata Kamsky in 1996. The PCA subsequently collapsed, however, as did Kasparov’s next independent venture, the World Chess Association.

Meanwhile, the FIDE continued its tournaments. When world champion Ruslan Ponomariov took the title in 2002, he was the youngest chess grandmaster in history at the age of 18. In 2003, Ponomariov was to play Kasparov in a match that would once more create a single world champion, but Ponomariov backed out due to a contract dispute. He later lost his title to the current FIDE world champion, Rustam Kasimdzhanov, who is due to play against Kasparov in spring 2005, at a site to be determined. The winner of that match will be considered the undisputed world champion. In the meantime, Kasparov continues to play in tournaments and the FIDE lists him as the highest-rated chess player in the world.

Deep Thought

Of course, not all the great chess players are human. Given the fact that the game requires analyzing all possible current and future moves on the board to find the right one for a given situation, it’s not a surprise that computers make great chess players. Mathematician Claude Shannon was one of the first to pose the idea in 1949, and astute viewers have noticed the Discovery’s onboard computer, HAL-9000, playing chess against one of the astronauts during Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 movie “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

IBM’s Deep Blue was the first supercomputer created specifically to play chess. It took on Kasparov in 1996, beating him in the first game before losing three and drawing two of the next five. In 1997, an upgraded Deep Blue won two more games against Kasparov, becoming the first computer to soundly defeat a grandmaster. Since then, man versus machine contests have become more popular, with grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik splitting four games with Deep Fritz in 2002 and Kasparov splitting six with the Israeli computer Deep Junior in 2003, among many such matches.

Opening the Game. A match begins on a classically-styled chess board.

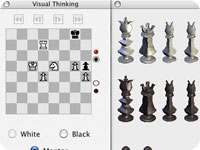

Planning Aid. The Visual Thinking box helps you work through not only your next move but also future ones.

That Hydrant is in Trouble. The dogs mightily converge.

Jonesie? A match against an AI player who obviously doesn’t have trouble deciding his next move.

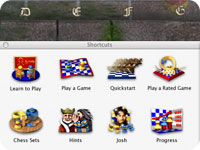

For the Children. The options you’ll find in the Kids’ Room.

Don’t Let the Clay Fool You. This contest ended quickly.

- Mac OS X version 10.2 (10.3 recommended)

- 700MHz PowerPC G3 processor (1GHz PowerPC G4 or higher recommended)

- 256MB of RAM (512MB recommended)

- 16MB video card

- 1.3GB of hard disk space

- DVD drive

- QuickTime 6