|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

By Brad Cook

Marc Atkin’s career as a digital filmmaker began when a few seemingly unrelated elements suddenly converged for him: the movie “2001: A Space Odyssey,” a “Hagar the Horrible” comic strip, and LEGO building blocks, which he rediscovered thanks to a friend who collects them. “I remembered a ‘Hagar the Horrible’ comic strip that spoofs ‘2001: A Space Odyssey,’” he recalls, “and thought I could do something like that in LEGO. Fueled by discussions with my housemate Ben, the story I was developing in my head started becoming more and more elaborate and started following the structure of the original movie more and more closely.” The Oldest Trick in the Book With a plan for his short film firmly in place, Atkin began creating “2001: A LEGO Odyssey” using a well-established cinematic special-effects process, stop-motion animation, the very technique that brought King Kong to life in the famous 1933 film.

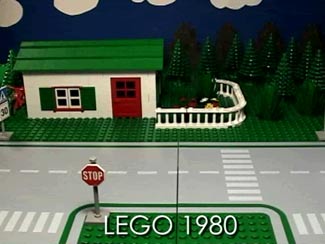

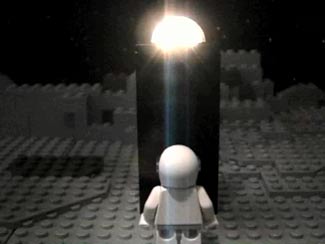

Atkin captured the action on a PowerBook connected to a Sony TRV 20 digital camera. He made his little LEGO people appear to move by snapping a digital photograph, then slightly changing their body positions before taking another shot. He repeated this process over and over, capturing each frame in iMovie as he snapped it. Eventually, he had recorded enough frames that he could play the footage at full speed, and the LEGO characters would appear as if they were moving. “I sent shots directly to the PowerBook so I could immediately see how they turned out and if they fit into the sequence properly,” Atkin explains. “The great thing about using a laptop was that I could move it to where my camera and scenes were set up.” Journey Through LEGO Time Like Stanley Kubrick’s original film, Atkin’s “2001: A LEGO Odyssey” begins with the dawn of man—only Atkin has renamed it “The Dawn of LEGO.” One primitive human, wandering through a jungle, comes across a stark black monolith standing among some trees, a pile of basic LEGO building blocks at its base. Curious about his find, the man inspects the blocks and then throws one into the air. The monolith spins until it becomes—thanks to the magic of movie editing—the wheel of a car. And, that quickly, we’re in the 1980s era of LEGO history. That edit is actually in homage to Kubrick’s signature jump cut in the original “2001,” in which a primitive man, following his encounter with the enigmatic monolith, throws a bone into the air. A few cinematic seconds later, the film cuts to a satellite floating through space. To further strengthen the allusion, Atkin also incorporates Kubrick’s classical music selections “Also Sprach Zarathustra” and “Blue Danube” in his film.

The rest of Atkin’s movie follows the history of LEGO, with various characters encountering monoliths and throwing bricks into the air. The final segment, “LEGO And Beyond the Infinite,” features an astronaut who enters a monolith and embarks on a LEGO-inspired journey through space and time, with a clever take on Kubrick’s famous shot of the Star Child at the end. “In many ways,” Atkin says, “the film is more of a critique of LEGO moving to more and more specialized pieces than it is a parody of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey,’ which I greatly admire. I just used the themes and structure of Kubrick’s film to illustrate a point.” |

Which makes sense, considering that the aberrant computer HAL 9000 is nowhere to be seen in Atkin’s version. “HAL makes sense in the original film, which is about the evolution of human intelligence, but he doesn’t fit in a film about the evolution of LEGO,” he explains. Completing the Odyssey Atkin shot some sequences against a green screen (see the sidebar for more information) and others (such as one sequence where he zooms into the monolith as an astronaut enters it and another in which a spinning red brick takes viewers from one sequence to the next) at full speed. When he finished filming, he exported the scenes as QuickTime movies, which he then edited in Final Cut Pro. Compared to using another computer platform to complete the project, Atkin believes “it was easier to do it on the Mac. FireWire is well integrated, and the capture capabilities of iMovie 2 were well-suited to my needs.” The digital filmmaker’s next project — a take-off on the film “Good Will Hunting” called “Good Will Skeleton” — is currently on hold while he completes his PhD in Artificial Intelligence at the University of Massachusetts, but his life-long interest in stop-motion animation likely won’t keep him away from LEGO, his PowerBook and a DV camera for too long. “I just have an interest in it,” he says of his fascination. “Maybe it’s the fact that you can make inanimate objects come alive.”

|

||

|

|

|||